The Metal Working Lathe And Its Uses. I. Description of the Lathe

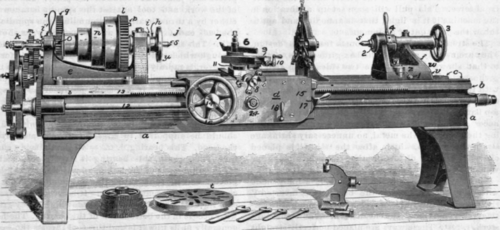

Figure 1. Metal Working Lathe.

Figure 1. Metal Working Lathe.Without exception, the screw-cutting lathe is the most universal machine tool that we have. Especially is this so when fitted out with various attachments for performing many operations usually assigned to the milling machine. This universality is not alone inherent with the design of the lathe, but it comes largely from the methods of design used in machine construction. It is far easier to turn a shaft to a cylindrical form than to make it square, or of other geometrical section, although a shaft of such a shape would answer the purpose quite as well in many cases. Of -course, in such cases as that in which a shaft is provided with a journal turning in a bearing, it is imperative that the section be circular.

The vast field of thread cutting is easily covered by the modern screw-cutting lathes, and threads of every conceivable section are readily cut. Nor is it uncommon to see the formation of a spiral groove, which in reality forms a thread, cut across the face of a piece of work. Threads may be readily formed on the conical surface of a piece, and in a great many cases threads are cut on worms for the transmission of power when the contour of the worm is far from a straight line.

By the aid of special forming cams attached either to the cross feed screw or elsewhere, certain predetermined shapes may be formed from solid blank material, and in repetition, with the assurance that each will be an exact duplicate of every other.

Nor does the limit of work end with the turning of pieces between the centers. The face plate aids in the performance of numberless jobs which, for the sake of speed, are assigned to either the shaper, planer or milling machine. But their work is no more accurate than what can be done on the face plate in facing the sides of a piece to absolute parallelism. Provided the face plate is true and the slide rest is absolutely parallel with it, delicate operations may be performed in this manner with ease and speed.

A great many lathes, especially the smaller sizes adapted for the useof amateurs, are fitted with milling attachments which widens the scope of the lathe still more. Gears, both of the spur and bevel variety may be readily cut, while cutters, reamers, and other special forms may be made.

The tool carriage may be easily fitted with a saddle upon which cylinders may be strapped and by the aid of a boring bar swung between the centers, bored to a true cylindrical surface, the feed of the carriage moving the work to the cutter. In this respect it occupies the place of the horizontal boring mill, while the shaper milling machine and drill press are each di-visted of certain lines of work usually assigned to them as belonging to their particular field.

It is the intention to treat in these articles the various operations that may be performed on the lathe, as well as the other machine tools in common use in the shop. The various parts of the lathe, its construction and method of operation will first be considered.

As it will be impossible to cover in the space available, every type of American lathes, a representative will be taken that lies midway between the very large and the small machines, and one that is not provided with all the new change gear features of convenience will be described at some future time. Fig. 1 shows very clearly such a lathe, and the letters of reference indicate the various parts to be spoken of in detail.

The bed of the lathe, a, is one of the most important features. While it does not appear at first sight to require any very great skill to make a metal form that will support and guide the carriage, a more intimate study of its construction will show many points where cheap lathes "fall down" when the test of heavy work is applied. The heavier the bed the greater solidity given to the machine, but not necessarily stiffness, which is purely a point of design. When a piece is supported between centers and revolved rapidly, as is usually the case in finishing the surface with emery and oil, any irregularity of form will cause a serious pull from from one side to the other, due to the centrifugal force. This pull will soon set up a vibration in the machine if it is light, that is annoying and apt to throw the parts out of alignment.

The strength of the bed is alone a feature of design. They are usually made of the box-girder form, similar to that shown in Fig. 1, the two sides being tied together at frequent intervals by the struts cast integrally with them. There is a flange at the top and bottom of each side which gives lateral stiffness, and upon the top flange the carriage usually moves. Great care is necessary in the casting of these beds to see that during the cooling of the metal, no unnecessary shrinkage strains are set up, which, after the "skin " is planed off, will cause a distortion that may in time grow worse.

The upper side of the top flange, b, is usually made with one or two, (two in the best forms) inverted V ridges, which form the ways, c, upon which the carriage, d, moves, and the headstock, e, and the tail-stock, f, rest. These ways are planed perfectly straight and true, and they form the guide for the tool, and, unless they are in perfect truth, the work will not be straight. In some forms of lathes there are no ways on the rear top flange, the carriage resting on the flat surface. One point of argument in support of this method is that the expansion of the struts has no tendency to lift the carriage and cause it to run on one side only of the the two Vs.

The greatest wear on these ways naturally takes place near the headstock, while that portion towards the tailstock end may not be worn in the least. Of course the majority of the work is short and the movements of the carriage are greatest at this point. The best makes of lathes provides an extra long bearing for the carriage, which obviates this difficulty to a great extent. There is now on the market a new toolsteel way that may be attached to a lathe bed. This-may be renewed when worn and, since it can be hardened, greatly lengthens the life of the lathe within accurate limits, although there are few lathes that will outwear the ordinary cast iron ways. By the time they have served their period of usefulness, every bearing and gear has become badly worn.